In their fourth annual series on real estate investment, Paul Chases, Micky Yang and the corporate real estate team at Herbert Smith Freehills LLP team up with tax and funds colleagues for three new articles – beginning with how to structure a joint venture into a joint venture.

In previous years we have noted the prevalence of joint ventures (jvs) in the UK real estate market (for both investment and development projects). There are several well-established reasons for this.

In an uncertain economic landscape, it is a way of sharing risk and reward. It also enables parties to share contacts, experience and expertise. It is easy to see how, particularly for an overseas investor that is new to the market, joining forces with a reputable UK real estate investor or developer with a strong track record would be an attractive proposition.

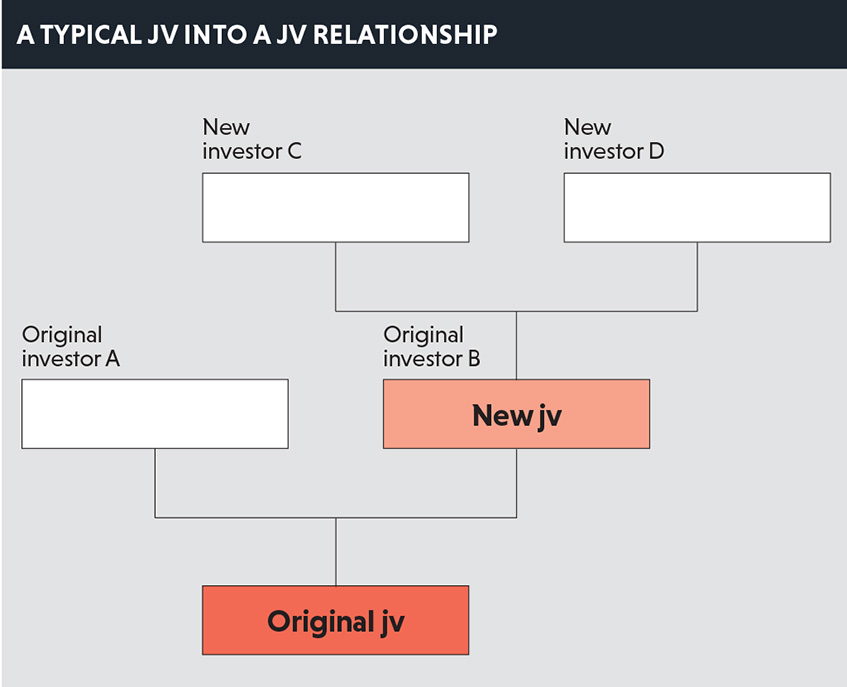

A noticeable development in the UK real estate market that we are seeing more frequently is the “jv into a jv”, whereby new investors form a jv (the new jv) that itself invests in a pre-existing jv (the original jv) entered into by the original investors.

Typically, a new jv is formed when the parties wish to reduce their exposure to an investment and bring in new investors while preserving the decision making, funding and liquidity arrangements agreed between the original investors in respect of the original jv. In other cases, it may be the result of a successful jv that develops into a platform for multiple-party investment.

In most cases, negotiating and completing a new jv (with multiple parties) that invests into a pre-existing jv is complex work. For example, the original jv may be a two-party 50:50 jv, but the new jv could in fact be a tripartite (eg 10:40:50) arrangement in respect of which each party will have different commercial interests and ultimately different rights and obligations.

Other dynamics will also have an impact on complexity. The type of new investors involved can vary (listed vehicle, private equity fund, institutional investor, pension fund, sovereign wealth fund, high-net-worth individuals, etc). The commercial position or risk profile of such new investors (which will be influenced by corporate culture and, to a degree, nationality) will have a real impact on the complexity of the arrangement and negotiations (particularly as the governance, funding and liquidity requirements of the parties are often not aligned).

The new investors will need to align their positions in the new jv with the original jv. This will usually require extensive analysis and negotiation. Below are some of the key aspects that will require attention.

Decision making for the new jv

When negotiating the new jv terms, the new investors will need to ensure the terms of the new jv dovetail in every way with the terms of the original jv, so that the new investors know, from the outset, what mechanisms will apply to determine the will of the new jv in exercising or waiving a right (or voting in favour or against a particular resolution) concerning the original jv.

In order to do this effectively, the new investors will need to consider every instance in which a decision or action by the new jv is required for the original jv.

On a practical level, care should be taken to ensure that the periods for calling board meetings and resolving deadlocks in respect of the new jv are sufficient to allow the new jv to react within the timescales envisaged in the terms of the original jv.

One of the biggest potential issues for the new jv is deadlock, simply because deadlock on a decision at the level of the new jv could well prevent the new jv dealing with matters in respect of the original jv (very much to the detriment of the original jv and any real estate investment or development project relating to it).

Deadlock resolution mechanisms can often be long-winded and provide an unsatisfactory outcome for the jv parties (particularly if this gives rise to a forced exit at a point in time before the jv parties were intending to sell – for example, before a development project has completed and reached stabilisation). It is therefore important for the new investors to consider and agree upfront (to the fullest extent possible) a fall-back position should the new investors disagree on a particular matter concerning the original jv.

If the new investors cannot do so, then the best commercial (and least volatile) position for the jv parties may simply be to exercise the new jv’s rights in the original jv in a manner that maintains the status quo. The appropriateness of this will need to be carefully considered on a case-by-case basis.

Board representation

In most cases, the new investors will probably want to be represented on the board of the original jv or (at the very least, if one of the new investors is a minority party in the new jv) have the right to appoint an observer to keep abreast of the affairs of the original jv. The terms of the original jv will need to accommodate this and will require amendment to regulate how the new jv will appoint or remove directors on the board of the original jv.

The lists of reserved matters relating to the relevant real estate investment or development project (being those matters that require unanimous approval or some other percentage threshold for agreement) will need to be considered in the new jv alongside the original jv to assess how they will (or should) operate side-by-side. Where both the new jv and the original jv are 50:50 jvs it is likely that the list of reserved matters at both levels will be similar (if not identical). However, they will almost certainly be very different in circumstances where the new jv is a tripartite or multiparty arrangement and the original jv is 50:50.

This will require careful analysis and will often involve a commercial discussion on the extent to which the new investors with a smaller stake in the new jv should have a say on the reserved matters (as they apply to the original jv). Put another way, this will involve an assessment of what the “minority protections” of the new investors with a smaller interest in the new jv should look like.

Conflicts

Conflicts tends to be another area in respect of which a jv into a jv results in dynamics that will need to be considered in negotiating the new jv terms, while reviewing the original jv terms.

Often the entry into certain material contracts by any jv will constitute a reserved matter requiring unanimous agreement or a specified majority vote of the relevant jv parties or their nominated directors.

However, where the counterparty to such a contract is one of the parties (or one of its affiliates), this often amounts to a conflict matter in respect of which the conflicted party (or its board representative) are not entitled to vote.

A new investor will probably want to ensure that contracts to be entered into between the original jv and any of the new investors (or their respective affiliates) constitutes a conflict matter affecting the new jv. The way to deal with this is to ensure that the entry into a contract between the original jv and a new investor (or its affiliate) constitutes a conflict of that new investor at the level of the new jv so that decisions regarding such contract are, insofar as the new jv is concerned, taken by the non-conflicted new investor only.

This will be particularly relevant in circumstances where one of the new investors (or its affiliate) also happens to undertake the development management or asset management role relating to the property owned by the original jv (pursuant to contractual arrangements entered into between the relevant new investor – or its affiliate – and the original jv).

Default

The jv parties will need to consider how a default in respect of the new jv should affect the rights and obligations of the new investors in relation to the original jv. This is an important area as, in any context, the default in question (material breach, funding default, insolvency, change of control, etc) will be attributable to one particular jv party.

One solution is for the new investor in default to be disenfranchised (and therefore stripped of their decision making powers) in respect of the new jv (if the relevant breach of the new investor remains un-remedied after a certain period of time).

As an extension of this point – and, again, to use the example where one of the new investors (or its affiliate) is also a development or asset manager of the properties owned by the original jv – it might be that a material un-remedied breach by such manager under the development or asset management agreement constitutes a cross-default into the new jv (triggering disenfranchisement or buyout at the level of the new jv).

Liquidity at the top jv level

The original investors may wish to retain the liquidity rights originally agreed between them in the context of the original jv, such that they apply to the new jv. If so, they will need to make sure that the exercise of such liquidity rights (at the level of the new jv) does not trigger change of control provisions in relation to the original jv. It is particularly important to deal with this point head on if a change of control of the original investors would amount to a default under the original jv, leading to a buyout right in favour of the non-defaulting party.

Future articles in this series cover: how authorised contractual schemes (a form of fund) could play a key part in the UK real estate market in the future; and real estate investment trust conversion

Paul Chases is a partner and Micky Yang, Alex Wright, Nick David and Somers Brewin are associates in corporate real estate at Herbert Smith Freehills LLP